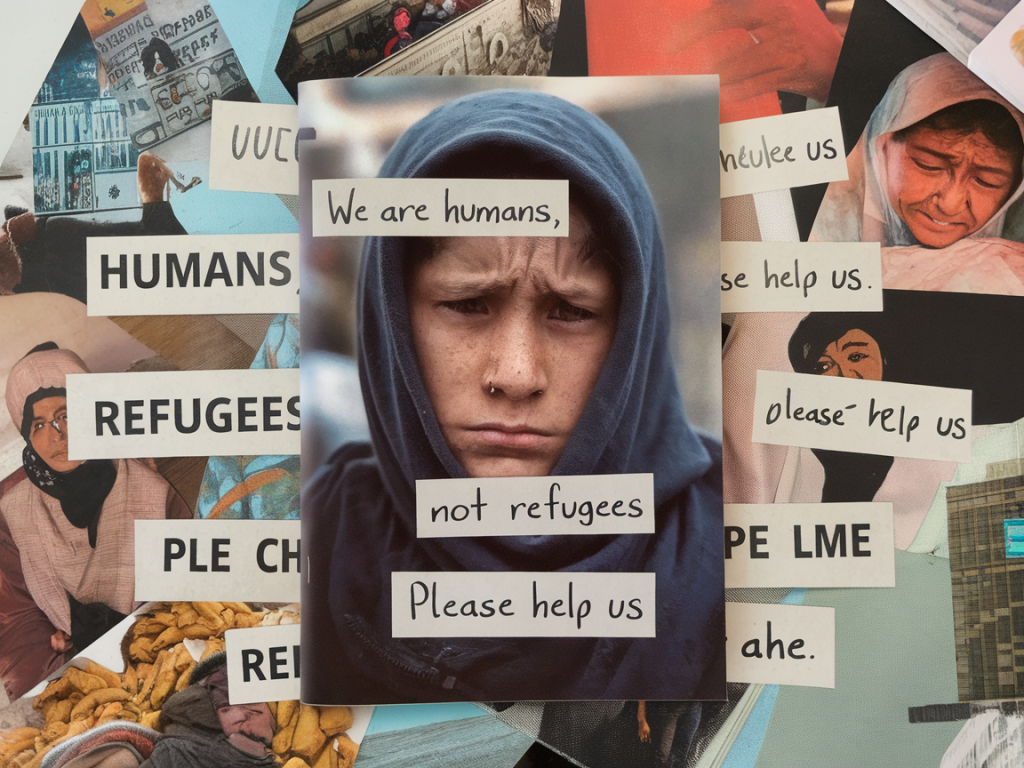

When I first encountered a stack of refugee-crafted zines at a small pop-up in a Parisian community centre, I thought I knew what I was looking at: homemade pamphlets, photocopied pages, hand-drawn covers. Aesthetically they belonged to the long and unruly lineage of DIY publishing. But the longer I read, and the more conversations I had with their makers, the less comfortable that simple categorisation felt. These objects — scribbled testimonies, folded narratives, collaged documents — were simultaneously personal archives, aesthetic experiments and deliberate instruments of political care. They resisted a single reading precisely because they were made to do so.

The hybrid life of a zine

In the refugee zines I’ve handled and helped circulate, three functions overlap constantly: evidence, art and strategy. Sometimes one of these is foregrounded — a zine that reproduces documents and dates might read like an activist dossier; another, full of illustrations and poetic fragments, reads like art. More often they fuse.

Consider a zine I worked with that combined a translated asylum interview transcript, photocopies of medical reports, and a sequence of ink drawings depicting the sea. The transcript and reports do the work of evidence — they anchor a personal experience in bureaucratic fact. The drawings open a sensory, affective register: the sea becomes a motif of loss, crossing and memory. And the zine’s very format — cheaply copied, folded for easy distribution at rallies and kitchens — is tactical. It is designed to be given away, stuck on walls, read aloud at meetings.

Why zines are such effective evidence

People often ask whether a handmade zine can really function as proof in an institutional sense. The answer is complicated. For legal proceedings, original certified documents are required; a little photocopied booklet will rarely satisfy a judge. But that misses half the point. Zines operate as social evidence.

So while a zine may not replace a lawyer’s file, it amplifies and humanises the facts that matter in legal and administrative processes. I’ve seen community legal clinics use zines as starting points for casework — not as substitutes for evidence, but as documentary leads and mood maps that help lawyers understand a client’s trajectory.

The aesthetic dimension: craft as legitimacy

There’s a persistent tendency to dismiss zines as amateurish; the DIY aesthetic is often read as lack, rather than as choice. But the visual language of refugee zines is meaningful. The gestures of collage, Ruled-line handwriting, photocopy distortion and deliberate typographic awkwardness are aesthetic choices that convey urgency, intimacy and defiance.

When a zine reproduces a torn ticket or a stamped page, the cost of production — cheap ink, a run printed on a Xerox or a Risograph — becomes part of the message. The grainy half-tones, occasional misregistrations and hand-trimmed edges signal material scarcity, mobility and improvisation. Those aesthetic conditions are legible: they say, without yet stating, that this is made by someone on the move, with limited resources, and that what follows is urgent.

I’m interested in how makers deploy specific tools — photocopying, Risograph printing, hand-stitching — not because they lack access to glossy production, but because those tools carry a register of authenticity and refusal. In my work with small presses and cultural organisations I’ve seen curators misread this as a lack of polish; the opposite is true. The form is integral to the content.

Zines as political strategy

Strategically, zines are nimble. They’re cheap to produce, easy to modify and designed for direct distribution. That makes them potent tools in contexts where visibility and narrative control matter.

One project I collaborated on involved a zine produced by an asylum-seeking women’s group. The zine was explicitly designed to be read in community kitchens where women met weekly. The readings generated safety, but they also created a set of testimonies that organisers could bring to local councils and MPs, backed by the moral force of communal witness rather than abstract numbers.

Ethics of collecting and curating refugee zines

As someone who curates and writes about cultural objects, I grapple with the ethics of archiving refugee zines. These are often intimate artefacts made under duress. Cataloguing them into institutional collections risks distance and misinterpretation. Yet leaving them invisible also consigns voices to erasure.

My approach has been practical and relational: work with creators, not about them. That means seeking informed consent for reproduction, co-curating exhibitions and ensuring that circulation benefits the makers — whether through direct sales, workshop stipends or visibility that leads to further opportunities. It also means resisting the temptation to aestheticise trauma for its own sake.

Where zines go from here

Digital platforms have changed distribution but not the fundamental logic of the zine: the hybrid mixture of memory, craft and activism persists. Many collectives now publish digital editions to reach audiences they could never meet physically; others double-run small printed copies alongside PDFs. Tools like simple desktop publishing, community risographs and affordable binding services make it easier than ever to produce meaningful material.

What stays with me is that refugee-crafted zines are not minor ephemera. They are cultural artefacts at the intersection of testimony, art and organizing. They teach us how to read evidence differently — not only as proof but as performative, relational and generative. If we treat them with the seriousness they deserve, they can do more than document; they can reshape the narratives that decide who belongs.