Handling sacred objects from other cultures is not an abstract curatorial puzzle — it’s a set of human relationships, obligations and risks that I have learned to take seriously through years of research, fieldwork and conversations with communities, artists and museum colleagues. When I think about ethics in cross-cultural collaborations, I try to keep one image in mind: not a trophy cabinet, but a circle of exchange in which the object sits within living practices, memories and duties that do not belong to me.

Why ethics matter beyond provenance

People often assume that ethical curatorship is primarily about provenance, repatriation and legality — and those are crucial. But I’ve found that ethical practice needs to reach further: to relationships, interpretation, display, access, and to the everyday choices that shape how an object is used, described and imagined. A legally acquired object can still be mishandled in ways that harm source communities; conversely, collaborative processes can transform how an object circulates and what it means to everyone involved.

Core ethical commitments I try to follow

- Prioritise relationship over ownership. Ownership is often treated as the decisive factor. In my work I prioritise cultivating ongoing relationships with knowledge-holders and custodians. That means repeated visits, long-term support, and sharing control over narratives.

- Practice humility. I approach collaborators as learners first. I am explicit about what I don’t know and open about my institutional constraints.

- Consent as process, not checkbox. Informed consent should be iterative. A single signed form is not enough; communities must be able to revise agreements as projects evolve.

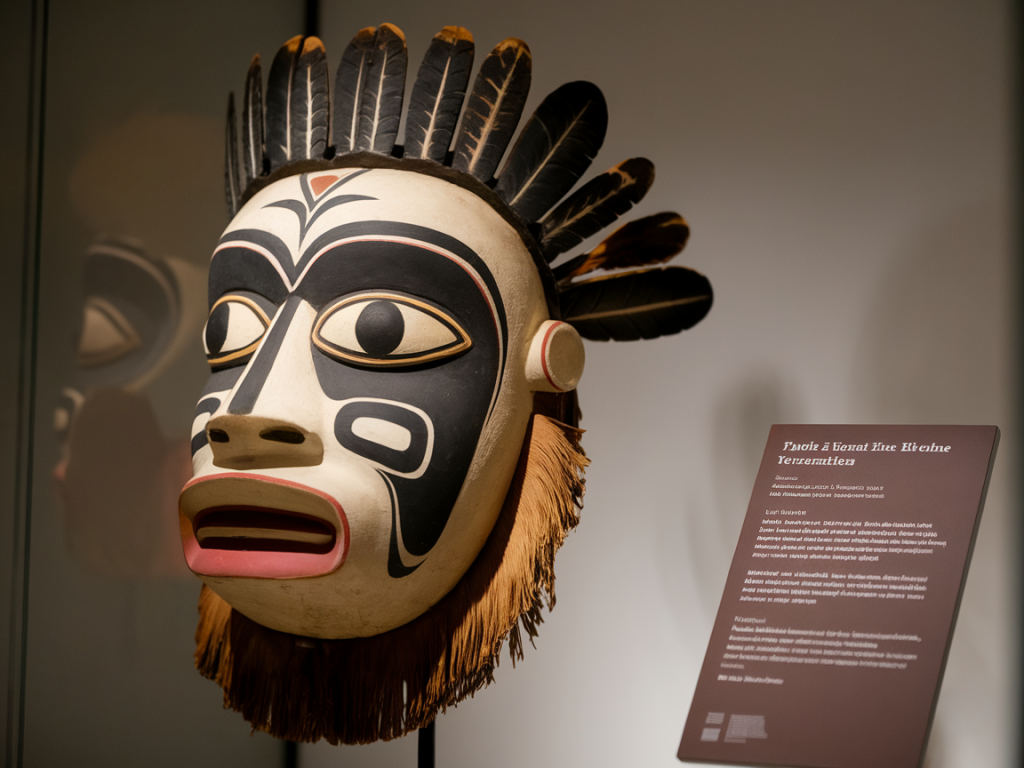

- Contextualise, don’t exoticise. I avoid sensationalising sacred objects. Interpretation should foreground cultural logic and contemporary significance, not only aesthetic appeal.

- Share authority and credit. Where possible I insist that community co-authors, co-curators and practitioners receive visible credit, compensation and intellectual recognition.

- Be transparent about funding and benefits. I disclose who pays for what, who benefits, and any commercial uses — particularly where brands or products are involved.

Practical steps in a collaboration

Ethics becomes tangible in the steps we take. Below are practices I’ve repeatedly found effective when working with sacred objects from elsewhere:

- Map stakeholders early. Identify elders, ritual specialists, local historians, artists, and younger community members. Not all voices are the same; include those who hold ritual authority and those who will be affected by exhibition outcomes.

- Negotiate terms publicly. Draft Memoranda of Understanding that are readable and available in local languages, and discuss them in community meetings. Treat these documents as living texts.

- Agree on display parameters. Some objects should never be put behind glass or under spotlight. Others may require contextual rituals before display. We have sometimes scheduled blessings or asked curators to step back from photographing certain items.

- Design interpretive text collaboratively. Labels and catalogue entries should be co-authored where possible. I often sit with community members over several sessions to test language for sensitivity and accuracy.

- Address circulation and digitisation carefully. Digital replicas, photographs or 3D models can increase access but also risk misuse. We negotiate licences that specify who may reproduce images, for what purposes, and with what attribution.

- Compensate fairly. Honoraria, revenue-sharing, and funding for local heritage projects are small steps toward justice. I push institutions to include project budgets for community remuneration.

Hard questions I ask before proceeding

Every project raises knotty choices. I try to make them explicit and discuss them with partners.

- Who is authorised to speak for the object’s community, and how do we include dissenting views?

- Will display alter an object’s ritual efficacy or social standing?

- What are the risks of public exposure — theft, commodification, misappropriation?

- How will we handle requests for repatriation or restrictions on access?

- Are there gendered or age-based restrictions that impact who may see or handle the object?

Casework: an example from practice

In a recent project involving carved ritual objects from a community I’ve worked with for years, we started with a simple principle: no exhibition without ceremony. That meant scheduling a period in which objects remained under community custodianship while elders decided which items could be displayed and under what conditions. We agreed that certain objects would be shown only to adult visitors, accompanied by contextual panels co-written by local speakers. We also negotiated a revenue-sharing model for ticket income and a small fund for cultural education in local schools.

One practical outcome was a set of display conditions embedded in the loan contract: designated handling protocols, photography restrictions, and a clause requiring the museum to pause the exhibition if community circumstances changed. These stipulations were unusual in my institution six years ago; now they feel essential.

When commercial interests appear

Brands and commercial partners can amplify attention and resources but can also distort sacred meaning. I’ve declined collaborations where branding would reduce objects to aesthetic motifs or where commercialisation threatened ritual secrecy. When a partnership is appropriate — for instance, with a responsible publisher or an ethical design label — I insist on contract clauses that protect iconography, limit merchandising and ensure royalties or contributions to community projects. Working with publishers like Thames & Hudson or specialist ethical platforms can be valuable, but the contract must reflect community priorities, not only market logic.

Tools I use to keep ethical choices visible

| Tool | Purpose |

|---|---|

| MOU templates | Formalise shared decisions, display permissions and compensation |

| Consent checklists | Ensure iterative consent at display, digitisation and publication stages |

| Community advisory boards | Provide ongoing governance and dispute mediation |

| Exhibition pause clauses | Allow response to evolving cultural or political circumstances |

I don’t think ethics can be reduced to a toolkit alone — but tools help translate principles into accountability. They also create traces: records that I and partner communities can return to if questions arise.

Navigating disagreement and ongoing learning

Disagreement is inevitable. I have sat through meetings where elders disagreed among themselves about what should be shown, or where younger activists demanded more radical transparency than older custodians preferred. My role is rarely to adjudicate; it’s to make sure these disagreements are visible and that institutional power does not suppress them.

Above all, ethical curatorship of sacred objects is a practice of listening, patience and reciprocity. It’s work that requires institutions to cede authority, accept messiness and commit resources for the long term. I’m still learning — and I try to say so publicly — because humility and accountability are the only reliable guides I’ve found when working across cultural boundaries.