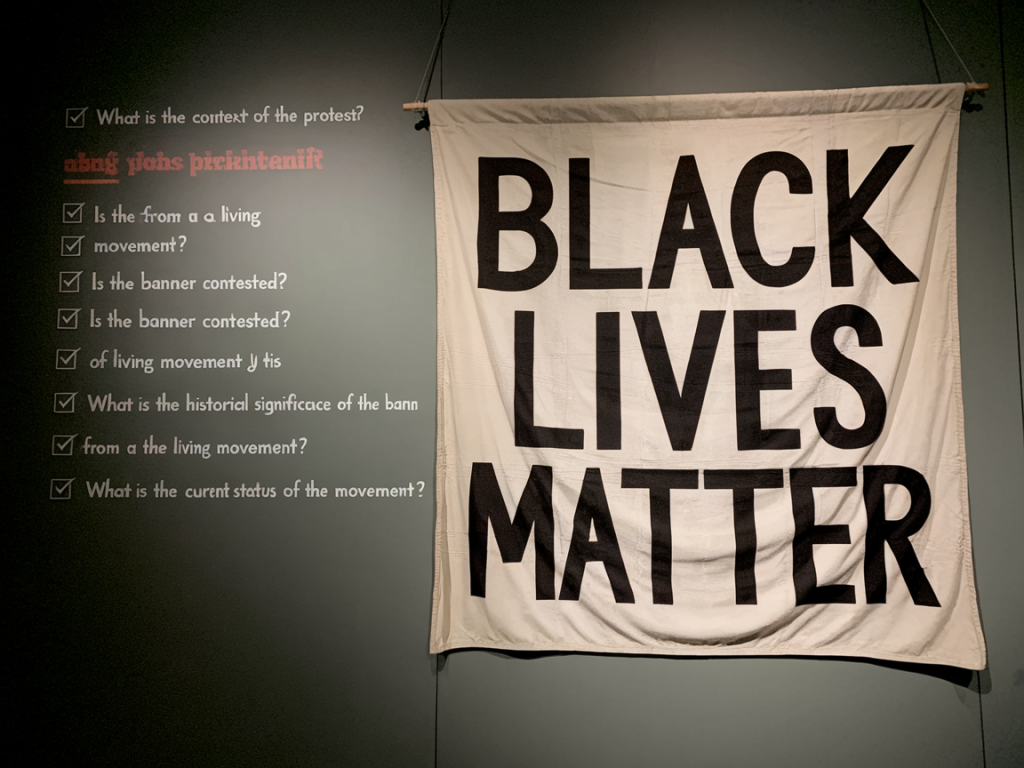

I remember the first time I stood in front of a protest banner that had been part of a living campaign — its fabric still creased from repeated folding, the paint slightly faded where hands had gripped it. It felt less like a neutral object in a vitrined past and more like a still-beating civic organ. As curators we are often asked to put such materials on display: banners, flags, placards, and other ephemera that carry the urgency of ongoing struggles. The ethical questions come fast and ruthless. Who owns the story? Who is centred? Could the display harm the people involved? How do we avoid extracting activism into a sanitized spectacle?

Why a checklist matters

A checklist isn’t a substitute for judgement, but it does force you to slow down and interrogate the assumptions behind a display. In my work with museums and community partners, I’ve found that a clear, shared set of steps helps prevent tokenism, legal missteps and — importantly — harm to living participants. Below are the pillars I return to when advising institutions or curating shows that include contested protest banners.

Principles to keep front of mind

- Do no harm: foreground safety and wellbeing of people connected to the banner.

- Agency: prioritise the voices of those who created, carried or were represented by the banner.

- Context over spectacle: avoid presenting protest material as mere aesthetic objects divorced from cause.

- Transparency: be open about provenance, partnerships and curatorial choices.

- Reflexivity: acknowledge institutional power, biases and potential conflicts.

An ethical checklist for displaying contested protest banners

Below is a practical, step-by-step checklist that I use with teams. It’s designed to be iterative — you’ll revisit items at multiple stages of a project.

| Stage | Questions to ask | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Initial contact | Who owns or claims the banner? Is the movement still active? Are there ongoing legal concerns? | Document provenance, reach out to known participants, check public records and media; pause if the banner is evidence in a legal case. |

| Consent & co-curation | Have creators/carriers given informed consent for display? Do they want involvement in interpretation? | Obtain written consent where appropriate; offer co-curation roles, shared credit and revenue if relevant; respect refusals. |

| Risk assessment | Could display expose individuals to retaliation? What are data protection implications? | Conduct safeguarding and data privacy checks; anonymise names if requested; set up support contacts. |

| Contextualisation | How will historical and political context be presented? Who narrates it? | Include multiple voices (oral histories, community statements, critics); avoid neutralising rhetoric that strips urgency. |

| Display & interpretation | Does the physical presentation respect the object's integrity and meaning? | Use conservation best practice; avoid aestheticisation that erases struggle; provide accessible interpretive material. |

| Duration & aftercare | What happens after the exhibition ends? Who controls future use? | Agree exit strategies, loan returns, digital archiving rights; share copies of documentation with communities. |

Practical steps and red flags

- Start with relationship-building: a respectful conversation with movement representatives should precede acquisition or loan paperwork. I’ve seen projects flourish when organisers co-write labels or contribute audio testimonies.

- Get informed consent that’s specific and revocable: consent isn’t a one-off checkbox. Make agreements time-limited and reversible where possible. Offer options: public exhibition, closed study access, or display with anonymisation.

- Map stakeholders: identify creators, carriers, allied organisations, critics and people who might be harmed by exposure. Invite them into advisory roles or at least consult them.

- Be honest about institutional position: some museums have relationships with local authorities or funders that conflict with a movement’s aims. Disclose these ties and negotiate how they affect curatorial choices.

- Consider security and confidentiality: a banner that names, exposes or incriminates individuals might put them at risk. Remove identifying details if requested, or use digital surrogates in public zones.

- Preserve agency in interpretation: avoid single authoritative labels. Use first-person statements, recorded interviews, and co-authored wall texts.

- Don't aestheticise the trauma: treating a banner as a “beautiful object” can strip it of meaning. Maintain visible signs of use — creases, stains — and explain them.

- Set a clear loan and reuse policy: specify who can reproduce images, for what purposes, and under what conditions. Creative Commons is an option, but check with rights-holders.

- Plan for longevity and repatriation: agree what will happen after the exhibition — return, long-term loan, digitisation with community access, or transfer of custody.

- Legal vetting: check libel, copyright, and data protection laws. In contested cases, seek legal counsel — better to delay than to harm lives.

Interpretation that centres living voices

Interpretive strategy matters as much as ethics. When I curate contested materials I aim to give the floor to participants. That can mean oral histories played near the banner, quotes from organisers on labels, or collaborative film projects shown alongside. Where possible, give financial support to contributors — an honorarium or fee for their expertise. Credit them clearly, not buried in small print.

Digital tools can help: high-resolution surrogates, interactive timelines and linked oral histories allow sensitive materials to be shared with layered access controls. Platforms like Omeka or CollectiveAccess are useful for co-curated archives; they let communities manage permissions and metadata.

When display may be inappropriate

Sometimes the right decision is not to display. Recentness, ongoing legal proceedings, direct threats to individuals, or explicit requests from creators to avoid public exhibition are valid reasons to decline. Transparency about why you’re not exhibiting — recording the decision process and sharing it with stakeholders — is itself an ethical act.

Curating contested protest banners demands humility, patience and a commitment to justice over spectacle. The checklist above is not exhaustive, but it’s a framework that helps protect people, centres those whose labour created the object, and preserves the banner’s political life beyond the museum gallery. In practice, each case will be unique; the only universal rule I’ve learned is to listen first, then act with care.